|

| There’s a very real chance that in the not-too-distant future, the elephant will trumpet its last. (Image via Goodreads) |

Its loud and distinctive croaking now exists only in recordings. It was one of hundreds of animals that disappeared from the planet last year as human-driven climate change, pollution, and other forms of habitat destruction ravaged ecosystems.

Javan rhinos, orangutans, sea turtles, saolas, pangolins, and elephants are all dying out. Make no mistake: this is a crisis that will have profound downstream consequences for humanity.

Javan rhinos, orangutans, sea turtles, saolas, pangolins, and elephants are all dying out. Make no mistake: this is a crisis that will have profound downstream consequences for humanity.

Ray Nayler focused his best-selling novel The Mountain In The Sea on this extinction crisis, depicting the extirpation of sea life from the oceans and its impact on humans. But despite the grim subject, the book offers an undercurrent of hope. His new novella The Tusks of Extinction acts as a darker, angrier, possibly necessary counterpoint to the earlier work.

“The Mountain in the Sea had its roots in the ecological preservation work I engaged in in Vietnam. That work was preventative and positive, working with youth and with environmental activists to protect the Con Dao Archipelago,” Nayler explained by email in early January. “The Tusks of Extinction has its roots in my experiences in Vietnam dealing with the illegal ivory trade and the trade in rhino horn. That work exposed me to the grimmest realities of human greed, ignorance, and exploitation. The enormity of the slaughter of elephants and rhinos for the sake of useless trinkets and the stupidest pseudo-medicinal ideas.”

The result is an uncomfortable read that will resonate with many and deserves serious consideration in every award category for which it is eligible. It’s science fiction deeply rooted in truth … and the current truth hurts.

As the book begins, scientists are recreating mammoths as a last ditch effort to keep the elephantidae family in existence. Siberia provides isolated stretches of open country, improving the odds for the wild megafauna. Since elephants — and their mammoth cousins — depend on generational knowledge to survive in the wild, the project is forced to recruit the recorded consciousness of a long-dead elephant conservation activist and researcher.

The novella follows three narrators who offer differing perspectives on an attempt to reintroduce the wooly mammoth into the wild: murdered elephant researcher Dr. Damira Khismatullina, uploaded into a mammoth matriarch; young apprentice poacher Syvatoslav; and ultra-rich big-game hunter’s spouse Vladimir.

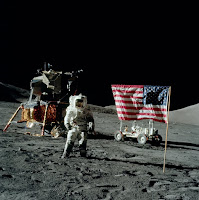

|

| About 100 African elephants are killed every day to fuel the illegal trade in ivory. The villain — as is often the case — is rapacious unchecked capitalism. (Image via Science.org) |

While humanity’s role in mass extinction is the main theme of the novella, an important sub theme is the relationship between senses, memory, and self identity. After her resurrection in the mammoth, Damira’s experience of the world is radically different, as is her relationship with memory. Assumptions about mind-body dualism are baked into the SF trope of uploading consciousness, and it’s refreshing to see these assumptions challenged.

“In a large part, The Tusks of Extinction is an exploration of the embodiment of mind, and also of the physical reality — the enormity — of our embodiment in the world,” Nayler says. “The mental changes Damira undergoes as a mammoth are a rebuttal of the idea of mind as separate from body and the sensory apparatus. The Tusks of Extinction is an expression of my anti-Cartesian view of the world. We exist in a physical body which exists in an ecosystem. The idea that we are floating intellects which can do as we will is one of the most damaging in human history: our lives are contingent, at all times, on physical reality and our place in it. The realization of that demands a corresponding ethics.”

The rationale behind the fictional project is expertly mapped out; research has shown that wooly mammoths enabled arctic ecosystems to store more CO2 than they otherwise would have. Having the mammoths back in the environment would disperse seeds, and increase resilience to climate change. Nayler gets the details right, and this helps make his larger arguments more believable and compelling.

Grounded in his experiences, Nayler offers insights about the social and economic conditions that lead to poaching. Svyatoslav, for example, is written with compassion and in a way that reflects on the endurance of those who lack the power to change a system that does not value their lives.

Hitting bookstore shelves during a decade when a significant portion of the SFF community seems to be seeking out comfort reads and hopepunk, The Tusks of Extinction may not appeal to all genre readers. But sometimes, sorrow is warranted and sometimes, there’s value in righteous anger.

It’s worth being angry about the potential loss of 44,000 species. As Nayler puts it: “We are intellectual animals with grand capacities, capable of living ethically and morally. It's time we used our brains to act in ways that prove we deserve to be on this planet, and that the human experiment is not doomed to be a destructive failure.”

We hope this novella finds the readership it deserves, and helps motivate some readers to take action.