|

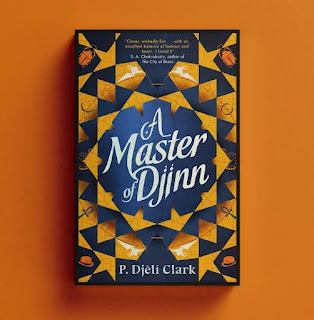

| The UK edition of Master of Djinn sports a cover that is as epic as the contents. The designer Matthew Burne deserves kudos. (Image via Little Brown Book Group) |

Set decades after magic was returned to the world by 19th-Century wizard al-Jahiz, these stories follow detectives who are tasked with solving supernatural mysteries.

This time, protagonist Fatma el-Sha’arawi is tasked with solving the murder of an important foreign dignitary, Lord Worthington, and the possible return of al-Jahiz himself.

What elevates the work is Clark’s use of the premise for confident explorations of colonialism, racism, and sexism. One member of our book club flippantly described Master of Djinn as being “from an alternate history where The Dresden Files bothers to say something interesting.”

Alternate history often doesn’t have a deep enough toolbox with which to examine and challenge historical power structures. Colonialism, patriarchy, and structural racism are so ingrained in the cause-and-effect patterns of real-world history that it’s difficult to find plausible allohistorical points of divergence in which these forces are subverted. In short, it would take magic of the sort that enriches Master of Djinn to tackle these entrenched forces and their myriad complexities.

The fantastical elements of Clark’s Egypt are imbued with a deep sense of history. While this book isn’t precisely an alternate history (as many purists of that genre will argue that any story that involves magic cannot be alternate history), Master of Djinn’s worldbuilding is complex enough for the reader to feel that there is a real past and a real future to this society.

In fact, this living, breathing history might be the most engaging character in the book. It’s a world full of sky trams, clockwork angels, and jazz clubs. Clark has skillfully woven worldbuilding details into the narrative that made it seem effortless and natural. It helped, of course, to have a character smitten with history and dedicated to sharing that knowledge.

An interesting parallel could be drawn between Master of Djinn and Rockne S. O’Bannon’s Hugo-shortlisted dramatic presentation Alien Nation. These are stories that deal with police investigating mysteries in a society that is adapting to the arrival of alien beings. In both cases, there are strong elements of social criticism and the use of non-humans as a metaphor for cultural barriers.

|

| P. Djèlí Clark — also known as Dr. Dexter Gabriel — holds a PhD in history and teaches at the University of Connecticut. This education is evident in the richly layered history that he crafts in Master of Djinn. (Photo by Peter Morenus via UConn Magazine) |

While the central mystery of the book, and most of the characters, are mostly enjoyable they are also largely unremarkable. For some readers, the relentless description of the flawlessness, stylishness, and incredible competence of the protagonist became tiresome. Likewise, Fatma’s much-trumpeted skill as a detective is undermined by how selectively observant she was, and how much of the plot depended on her missing obvious clues. Those who are seeking an engaging mystery may be disappointed, for the reasons above and also because this is not a page-turner typical of that genre.

It did seem odd that the novel was peppered with so many references to the previous stories set in the same world. Those who had not read the preceding works were left feeling that there was something missing.

But for many in the book club, these quibbles are overshadowed by the engaging motivations of those who committed the crime, the well-thought out tensions in the world’s international politics, and the skillful interrogation of power dynamics. Digressions into a possible alliance between the Kaiser and Ottoman Empire, and speculation about what Lord Worthington may have been up to before his demise are all quite interesting.

A Master of Djinn is a strong Hugo finalist that may be near the top of some of our ballots.

It did seem odd that the novel was peppered with so many references to the previous stories set in the same world. Those who had not read the preceding works were left feeling that there was something missing.

But for many in the book club, these quibbles are overshadowed by the engaging motivations of those who committed the crime, the well-thought out tensions in the world’s international politics, and the skillful interrogation of power dynamics. Digressions into a possible alliance between the Kaiser and Ottoman Empire, and speculation about what Lord Worthington may have been up to before his demise are all quite interesting.

A Master of Djinn is a strong Hugo finalist that may be near the top of some of our ballots.