This blog post is the eleventh in a series examining past winners of the Best Dramatic Presentation Hugo Award. An introductory blog post is here.

Star Trek’s dominance of the 1968 Hugo Award Best Dramatic Presentation shortlist is as much a reflection of the quality of the show’s first and second seasons (episodes from each were eligible), as it is evidence that it was an off-year for most science fiction on screen.

As noted by contemporaneous fan writers such as Ted White and Brian Aldiss, there were an extraordinary number of exceptionally terrible science fiction films in the theatres in the preceding year:

exploitation flicks like

Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women, broad comedies like Don Knotts’

The Reluctant Astronaut, and cheaply made filler like

Journey To The Centre of Time. Most of the televised science fiction was sub-par, though

Doctor Who’s Second Doctor had three of his best stories with “Tomb of the Cybermen,” “The Moonbase,” and “The Web of Fear.”

In terms of foreign-language cinema, there’s few stand outs. If it weren’t for

Star Trek, would Best Dramatic Presentation have recognized something like

Late August In The Hotel Ozone?

While some pundits decried the fact that the entire shortlist for the 1968 Dramatic Presentation Hugo was made up of

Star Trek episodes, none could offer credible alternatives to Roddenberry’s show.

“Non-

Star-Trek fanciers may be annoyed to see five

Star Trek episodes and nothing else on the ballot, but I’m happy enough,” Juanita Coulson wrote in

Yandro.

For the most part, it’s remarkable how well the shortlist holds up. It may all be

Star Trek, but there is a remarkable diversity of science fiction stories that writers were able to tell within the confines of the show’s “wagon train to the stars” format.

Reimagining

Moby Dick by way of Fred Saberhagen’s

Berzerker stories, Norman Spinrad’s episode

|

"Doomsday Machine" stands

the test of time as a solid

character study of obsession

and loss.

(Image via StarTrek.com) |

“Doomsday Machine” is a terrific adventure story that combines big science fiction ideas with memorable character moments. William Windom as Commodore Matt Decker is one of the all-time great guest appearances on

Star Trek.

On the other end of the spectrum, “The Trouble With Tribbles” is a more lighthearted episode about an agricultural shipment, a grain-eating pest, and Cold War tensions. The dialogue in the episode is memorably sharp with quippy lines like “hauled away as garbage,” “a very little joke,” and “an ermine violin.” Some contemporaneous fans complained that the tone was too unserious, but with the benefit of hindsight, the episode holds up well.

To us, a more questionable inclusion was the Season 2 premiere “Amok Time,” a weird melodramatic episode about Spock’s return to his home planet of Vulcan. For those who haven’t seen it recently, it’s a buck-wild bit of ritual combat between Spock and Kirk as they are forced to fight over a woman. The “woman as a prize” theme should have been unacceptable in the 1960s, and certainly doesn’t hold up well today, the writing is mostly quite flat, and the depiction of Vulcans as a mystical culture that uses gongs excessively could be read as having some ugly coded subtext. This is one of the worst episodes for Kirk as a character; it’s unsettling to watch Kirk pressuring a subordinate to reveal personal info.

Although the ‘alternate universe’ episode has become a staple for most SFF TV shows, when

Star Trek did

|

Kirk's visit to the darkest timeline

provided a template for all later

mirror universes on television.

(Image via StarTrek.com) |

it with “Mirror Mirror,” the concept was still fresh. With the introduction of the concept to mass media television, they also hit a high water mark. The quality of

Star Trek’s original cast shines through in this episode, as George Takei, Walter Koenig, and Leonard Nimoy all show why they would have been stars even if Trek had never made it to air. It must also be mentioned that guest star BarBara Luna is memorable as Lt. Marlena Moreau.

More has been written about the Hugo-winning episode, Harlan Ellison’s “City On The Edge of Forever,” than about probably any other single episode of televised science fiction. Given the weighty moral quandary (sacrificing love for the sake of history), and the solid character moments between the central trio of Spock, Kirk, and McCoy, the level of appreciation for the episode is understandable. What’s interesting is how quickly it was recognized as a classic, and immediately at the forefront of discussions of what should get the Hugo.

“City [on the Edge of Forever], which deservedly won the Hugo for best dramatic presentation, is probably the best drama, if not the best science fiction, ST has had to date, and I was happy to see it again” wrote Kay Anderson in her convention report.

What few complaints there were about a

Star Trek-full category focused more on who had been left off the ballot; pundits such as Doug Lovenstem of the fanzine

Arioch suggested that it was time for D.C. Fontana to win a Hugo Award (she would receive her only nomination 20 years later). Others noted the absence of “Devil in the Dark,” which is often regarded as one of

Star Trek’s finest hours (and certainly better than “Amok Time”).

For our cinema club’s re-watch of these episodes, we’d all gone in expecting to agree with this consensus. But in the end, none of us were convinced that “City On The Edge of Forever” was the best episode; two of us preferred “Mirror Mirror,” one put “Doomsday Machine” at the top of their list, while another rated “Devil In The Dark” the most highly.

But at the 1968 Hugo Awards, two things were inescapable:

Star Trek and Harlan Ellison. Five nominations to

Star Trek, three to works penned by Ellison, and five to works that appeared in a publication edited by Ellison. In retrospect, this win seemed inevitable.

“The Hugos: Bjo doesn’t win. Dave Gerrold doesn’t win. Larry [Niven] doesn’t win. Harlan wins. There

|

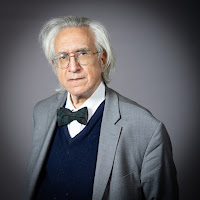

The head table at the 1968 Hugo Awards banquet

Philip Jose Farmer, Betty Farmer, Harlan Ellison

(Image by Len & June Moffatt via Fanac.org)

|

is no justice in this world. I like Harlan, but there’s a limit to how many Hugos he should win,” Sandy Cohen wrote in

Argus in October 1968. Ellison had ruffled his fair share of feathers throughout fandom, and it would eventually come to haunt him. But in 1968, Harlan Ellison was at the top of the SFF world, and probably his all-time most recognizable work took home the Best Dramatic Hugo.

The Best Dramatic Presentation shortlist in 1968 is a product of its time. It is likely that no SFF television show will ever have the impact that

Star Trek did that year, and it is equally unlikely that there will be another year with as few viable contenders for the prize. (A clean sweep of nominations in the category has also been rendered impossible by rules changes).

In short: an odd year for the Hugos, but one where it’s difficult to argue too vehemently against the judgment of the fans.