The black-clad implaccable figure of Judge Joseph Dredd looms large over the history of British comic books.

Ever since March 5, 1977 when he first graced the pages of the comic book 2000 A.D., Dredd has fought alongside Batman and gone toe-to-toe with The Predator, and generally provided a presence that has inspired two Hollywood movies, one animated television show, no fewer than eight video games, four table-top roleplaying games, and a line of Funko Pop! Bobbleheads. Dredd’s cultural impact and enduring appeal are clearly worth examining.

Police conducted a Judge Dredd LARP

in response to a trans-rights demonstration.

(photo by Olav Rokne)

In his new non-fiction book I Am The Law, British journalist Michael Molcher provides the character with an overdue analysis. He makes a compelling argument that Judge Dredd isn’t just the most important British comic book … it might be one of the most important works of science fiction, and maybe even social science fiction, of the past four decades

“What Dredd tackles is the fundamental nature of policing in society. Consequently, it’s a story that has asked deep questions about what kind of society we want,” Molcher says. “Dredd just gives such a prescient warning – such an important warning – about what we’re sliding into.”

Dredd was created by American expatriate writer John Wagner and Spanish artist Carlos Ezquerra in 1977. Each of these creators came to Great Britain having grown up in a country where the relationship between police and the broader public was more fraught than it was in the United Kingdom. Molcher argues that their creation of a militarized science fiction police officer who upheld a rigid and absolutist approach to law enforcement was fundamentally different from other contemporaneous cultural commentaries on policing. While characters like Dirty Harry, The Sweeney, and The Punisher all represented “the strong individual tired of the weak state, Dredd represents the strong state that is tired of the weak individual.”

The book depicts the creation of Judge Dredd as a response to the rising reactionary moral panics that engulfed British media in the late 1970s. Molcher seems to argue that comics provided a fertile ground outside of the “establishment” media for Judge Dredd writers like John Wagner and Alan Grant. It provided a platform from which they could offer pointed critiques that were later seen as prescient.

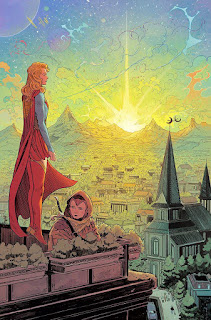

“Things that happen in [Judge Dredd] echo, copy, or pressage things that happened in real life maybe a week or two either side. These are comics that were written months before,” Molcher says. “It’s almost Cassandra-like.”Michael Molcher's deep dive into

philosophy and sociology elevates

I Am The Law to a must-read text.

(Image via the author's Instagram)

By understanding Judge Dredd, Molcher argues, we can understand the multifaceted political crisis we are facing today. Thus, it might also be considered an important work of social science fiction. Throughout the book, history, sociology, and cultural studies are woven together.

“When you look at the book Policing The Crisis by Stuart Hall — it’s about the moral panic around the mugging crisis of the 1970s -- you can’t help but realize that Hall and [Judge Dredd writers] John Wagner and Alan Grant are talking about the same things,” Molcher says.

Dredd was published when an ascendant right-wing press was stoking public fears about crime and safety in Britain. Through the mid to late 1970s, headlines trumpeted the idea of a “mugging crisis,” and chronicled the bloody exploits of the Yorkshire Ripper. Simultaneously, the reputation of the police was being eroded by a series of scandals in which abuse of power had come to light.

Molcher explores how this moment was reflected in contemporaneous pop culture and how Judge Dredd quickly differentiated itself from these other social commentaries. By depicting Dredd’s inhumane response to crime as an explicitly state-sanctioned activity, the comic’s writers suggest that the inhumane actions of real-world police are often implicitly state-sanctioned.

“There's a subtle kind of moral economy to Judge Dredd comics which can be easy to miss if you're there for the shooting,” Molcher says.

Despite having a cult following in the United States, Dredd has never had as large a following there as in Great Britain. In part this can be chalked up to the stories being published much later in America, in large volumes that only included the most commercially successful issues.

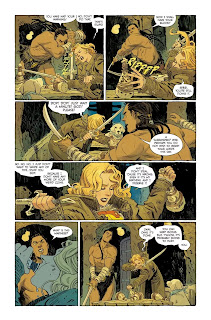

Early Dredd comics including The Cursed Earth

are put into historical context.

(Image via WhatCulture.com)

“America is always going to struggle with Dredd as a character. It has to do with the nature of the American action film, the nature of America's relationship with its police, and the desire to make Dredd into a hero when he's not.” Molcher says.

The book often makes for grim reading, especially when Molcher explores the global rise of authoritarianism and the decline of democracy. Chapters on how Judge Dredd responds to protestors — and how that’s now reflected in real-world police responses to activism — are chilling.

“This wasn’t the book that I’d intended to write,” he says, explaining that his original pitch to his publisher was a book more broadly about the history of Dredd. “I knew that the book would be about politics and that there would be an aspect of it that would be about criminology. But the more I read about the history of policing, the more I realized that this version of the book was unavoidable.”

I Am The Law may be the best primer for American audiences wanting to understand the phenomenon of Judge Dredd. It may also be one of the most important books about science fiction published this decade. Molcher has offered readers a dystopian non-fiction that matches the current moment.