|

| The second-most famous Kryptonian, Kara Zor-El finally gets the attention she deserves in Woman of Tomorrow. (Image via DC.com) |

Sadly, too many writers treat Supergirl as if she were just a gender-flipped Superman.

Like Superman, she was born on the doomed planet of Krypton. And like him, she is mostly invulnerable, has super strength, has various enhanced senses, can shoot lasers from her eyes, and flies around the planet saving people in distress.

Kara Zor-El grew up in the domed city of Argo. This city escaped the destruction of Krypton, and after several years Kara was sent to Earth to find her cousin Kal El (Superman), who had been sent there as a baby. There, she took up the mantle of Supergirl, and fought alongside Superman on various adventures.

Over the decades, writers have grappled with the conundrum of how to make the character interesting; varying her origin story, altering what her superpowers are, and occasionally removing the character from the shared comic book universe altogether.

With the 2022 publication Supergirl: Woman of Tomorrow, writer Tom King (Mr. Miracle, Human Target, Sheriff of Babylon) and artist Bilquis Evely (The Dreaming, Doc Savage, Wonder Woman) provide one of the more successful attempts to define the character not in relation to her cousin, but on her own terms. This story looks at what it means for someone to lose their family, their homeland and their culture as a teenager, and focuses on how she constructs meaning for herself.

It is probably the most compelling Supergirl story yet published.

Over the past 30 years, almost every major superhero has been deconstructed. Grim-and-gritty reboots, meta-commentary on comic books, and reframing of existing story arcs have been done often enough in superhero stories that postmodern comic book work has begun to look tired. What elevates Tom King’s work is that he tends to focus on the ‘hero’ more so than the ‘super.’ This is recontextualization, but not deconstruction. It’s examining the characters through a constructive lens. This can be seen in how he’s evolved Kite Man as a character, how he’s explored Batman’s marriage, and peered into Scott Free’s psychology. And now, how he’s focused on what motivates Supergirl.

|

| Tom King's work has previously inspired the hit TV show Wandavision on Disney+. (Image via Entertainment Weekly) |

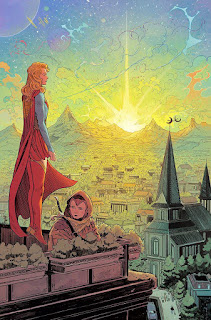

Woman of Tomorrow is told from the perspective of Ruthye — a young orphan on an alien world — who is seeking revenge for the murder of her father by a bounty hunter named Krem. In her quest for vengeance, Ruthye gets in trouble and must be rescued by Supergirl. Because she has never heard of Supergirl (or Superman) before, Ruthye provides readers a fresh perspective of the Kryptonian, essentially seeing her through new eyes.

Over the subsequent eight issues of the comic series, the duo track Krem across planets and star systems, deal with space pirates, and have adventures on interstellar public transit.

Supergirl takes time to help one of Krem’s victims dig graves for everyone he’s known, provides a therapy session to a grieving mother, and uncovers a genocide. Each of these adventures is a delay from her mission but is necessitated by a code of honour that compelled her to start the mission with Ruthye in the first place.

Krem proves to be an adept adversary. He figures out Supergirl’s vulnerabilities and strips her of her powers. This gives us a chance to see Ruthye’s own strength as she defends the titular heroine and faces her own trials, largely unaided.

These aren’t stories about saving the universe, defeating galactic tyrants, or challenges with world-shattering consequences. But the fact that the stakes are more personal shows what matters to Supergirl, and the human scale of the story makes it highly engaging.

|

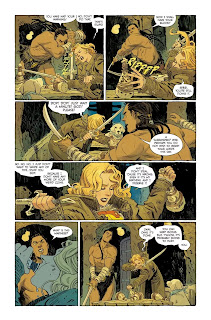

| Taverns, swords, heroic fantasy-style adventures. (Image via DC.com) |

On a technical level, this is a superhero comic book, but the writing takes much of its inspiration from heroic fantasy. This is a story about a sword-wielding hero and sidekick traveling across distant landscapes on a quest and getting pulled into side adventures. Given that it takes cues from the heroic fantasy work of Fritz Leiber, Woman of Tomorrow seems like something that would appeal to many Worldcon attendees.

This heroic fantasy influence is accentuated by the expressive artwork of Bilquis Evely and the talented colouring by Matheus Lopes, which bring the series to life. Evoking the best of Barry Windsor Smith’s sword and sorcery work for Epic Comics, Evely’s style is both detailed and energetic. The colouring provides a perfect counterpoint to the linework, transitioning from muted tones for more sombre scenes, to vivid and engaging palettes for the wild space adventures. The work is lush, inviting, and perfectly suits the tone of the writing.

In 2023, Warner Brothers announced their upcoming slate of movies based on DC comic books, and named Woman of Tomorrow as the direct inspiration for their next Supergirl movie. Although we cannot figure out how they might translate the visual poetry of Evely’s work, they couldn’t have chosen a better comic to adapt. Supergirl deserves to be more than a gender-flipped Superman, including on the big screen.

We’d love to see this earn a Hugo nomination.