This blog post is the twenty-sixth in a series examining past winners of the Best Dramatic Presentation Hugo Award. An introductory blog post is here.

|

| In 1982, audiences flocked to see Spielberg's watered-down and mawkish remake of Close Encounters of the Third Kind. (Image via Cult Following) |

There seemed to be a consensus that E.T. — a $360-million blockbuster box-office juggernaut — was going to win the award … though some fans such as Richard E. Geis (who himself won a Hugo that year) groused that they were, “sick of the Steven Spielberg juvenile sweetness-n-light approach to SF.”

On the Sunday evening of the convention at the Hugo Awards ceremony (which featured a crab feast), however, the audience reacted with stunned silence — and then rapturous applause — as toastmaster Jack L. Chalker read out that Blade Runner had taken home the trophy.

It was not an uncontroversial decision; Blade Runner seems to have been championed by old-school science fiction fans and those who wanted the genre to take itself seriously, while E.T. was the choice of more whimsical fans. One fanzine churlishly chalked up Blade Runner’s win to nostalgia and a desire to give a Hugo to the recently deceased Philip K. Dick.

|

| Not all science fiction movies of 1982 are certified classics. (Image via IMDB) |

It had been an impressive year for science fiction cinema. The Hugo shortlist featured classics like Blade Runner, E.T., and Mad Max: The Road Warrior alongside The Wrath of Khan (often regarded as the best Star Trek movie) and The Dark Crystal (which retains a cult following today).

Beyond the shortlist were even more important classics, almost too many to talk about in a blog post. John Carpenter’s The Thing remains one of the greatest science fiction horror movies ever made. Special effects juggernaut Tron kicked off the digital revolution in how movies were made. Don Bluth’s first movie as a director, The Secret of Nimh, is still beloved by younger audiences. Rainer Wenrer Fassbender’s Kamikaze 1989 brought the cyberpunk movement to Germany. French director René Laloux worked with famed illustrator Mœbius on an animated space opera Les Maîtres du Temps. John Milius brought Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian to the screen. In Poland, Piotr Kamler wowed audiences with the visually lush stop-motion of Chronopolis. Not to mention, that television shows Knight Rider and Voyagers! both hit the airwaves that year!

Rewatching these films with the benefit of 40 years of hindsight, the shortlist looks pretty darned good. Even Jo Walton (who has often griped about the Best Dramatic Presentation category at the Hugos) conceded that in 1983, “there’s not only a worthy winner in this category, but something that almost looks like sufficient nominees to be worth running it.”

The weakest movie on the shortlist is The Dark Crystal. Although the set design is lush and the technical details are impressive, the story is pedestrian and the dialogue is dull. It’s a standard fantasy epic in which ahobbit gelfling has to travel to mount doom the citadel and destroy a ring crystal shard. None of the characters are particularly memorable, other than in appearance.

Even early in his directorial career, George Miller’s talent for visual storytelling is evident in the kinetic, engaging, and over-the-top bonkers Mad Max: The Road Warrior. Watching it in the context of its era, it’s difficult to overstate how revolutionary it was for post-apocalyptic movies; compared to the frenetic violence of Mad Max, the previous decade’s offerings such as Omega Man, A Boy And His Dog, and No Blade Of Grass all seem quaint. Although we’re generally not fans of opening and closing monologues, Mad Max does enough visual storytelling to have earned its exposition. Despite his later descent into antisemetic buffoonery, it’s easy to understand why the young Mel Gibson became a star. Just 21 years old at the time of filming, he’s able to carry the movie on his performance.

Given that the franchise has become increasingly focused on nostalgia, it’s interesting to note that The Wrath of Khan is the first Star Trek film that is mostly looking at the past. Not only does the movie deal with an antagonist that had appeared in a previous episode, James T. Kirk (William Shatner) spends much of the film pining for the old days and contemplating his own mortality. One of the reasons this works is that — unlike another former Trek captain’s navel-gazing nostalgia fest — The Wrath of Khan also explores generational change. Some might argue that director Nicholas Meyer’s other Trek film is better but there’s a lot to love in this movie and it’s easy to understand why it placed second on the Hugo shortlist. It’s not just good Star Trek, it’s a good movie.

What aged less well, however, is E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial. Despite good special effects, and Steven Spielberg’s skill with lighting and shot framing, we might argue that it doesn’t meet the standards of science fiction or of storytelling that should be expected of a Hugo finalist — especially in a cinematic year as strong as 1982. The movie often feels like an overlong sitcom episode with a pedestrian alien plot and wacky elementary school hijinks. Moreover, most of the younger characters are surprisingly mean to each other pretty much all the time; dialogue is delivered as yelling which can be exhausting for today’s audience. That being said, it was the top-grossing movie of the year, so clearly it resonated with audiences of the day.

Beyond the shortlist were even more important classics, almost too many to talk about in a blog post. John Carpenter’s The Thing remains one of the greatest science fiction horror movies ever made. Special effects juggernaut Tron kicked off the digital revolution in how movies were made. Don Bluth’s first movie as a director, The Secret of Nimh, is still beloved by younger audiences. Rainer Wenrer Fassbender’s Kamikaze 1989 brought the cyberpunk movement to Germany. French director René Laloux worked with famed illustrator Mœbius on an animated space opera Les Maîtres du Temps. John Milius brought Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian to the screen. In Poland, Piotr Kamler wowed audiences with the visually lush stop-motion of Chronopolis. Not to mention, that television shows Knight Rider and Voyagers! both hit the airwaves that year!

Rewatching these films with the benefit of 40 years of hindsight, the shortlist looks pretty darned good. Even Jo Walton (who has often griped about the Best Dramatic Presentation category at the Hugos) conceded that in 1983, “there’s not only a worthy winner in this category, but something that almost looks like sufficient nominees to be worth running it.”

The weakest movie on the shortlist is The Dark Crystal. Although the set design is lush and the technical details are impressive, the story is pedestrian and the dialogue is dull. It’s a standard fantasy epic in which a

|

| The soundtrack to Mad Max is a bit too much like Yakety Sax for our tastes, but the visuals are great. (Image via SlashFilm) |

Even early in his directorial career, George Miller’s talent for visual storytelling is evident in the kinetic, engaging, and over-the-top bonkers Mad Max: The Road Warrior. Watching it in the context of its era, it’s difficult to overstate how revolutionary it was for post-apocalyptic movies; compared to the frenetic violence of Mad Max, the previous decade’s offerings such as Omega Man, A Boy And His Dog, and No Blade Of Grass all seem quaint. Although we’re generally not fans of opening and closing monologues, Mad Max does enough visual storytelling to have earned its exposition. Despite his later descent into antisemetic buffoonery, it’s easy to understand why the young Mel Gibson became a star. Just 21 years old at the time of filming, he’s able to carry the movie on his performance.

Given that the franchise has become increasingly focused on nostalgia, it’s interesting to note that The Wrath of Khan is the first Star Trek film that is mostly looking at the past. Not only does the movie deal with an antagonist that had appeared in a previous episode, James T. Kirk (William Shatner) spends much of the film pining for the old days and contemplating his own mortality. One of the reasons this works is that — unlike another former Trek captain’s navel-gazing nostalgia fest — The Wrath of Khan also explores generational change. Some might argue that director Nicholas Meyer’s other Trek film is better but there’s a lot to love in this movie and it’s easy to understand why it placed second on the Hugo shortlist. It’s not just good Star Trek, it’s a good movie.

What aged less well, however, is E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial. Despite good special effects, and Steven Spielberg’s skill with lighting and shot framing, we might argue that it doesn’t meet the standards of science fiction or of storytelling that should be expected of a Hugo finalist — especially in a cinematic year as strong as 1982. The movie often feels like an overlong sitcom episode with a pedestrian alien plot and wacky elementary school hijinks. Moreover, most of the younger characters are surprisingly mean to each other pretty much all the time; dialogue is delivered as yelling which can be exhausting for today’s audience. That being said, it was the top-grossing movie of the year, so clearly it resonated with audiences of the day.

|

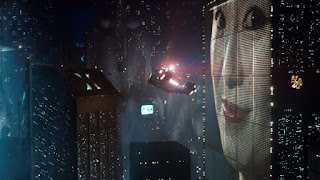

| Blade Runner is visually immersive, lush, and compelling. It's stood the test of time. (Image via IMDB) |

It’s also worth noting that the 1983 Worldcon was attended by an unusually large number of movie stars and cinema professionals. Makeup artist Rick Baker was in attendance to talk about Greystoke. Producer Gary Kurz (Empire Strikes Back) was there to talk about his Return to Oz. Jim Henson attended his second Worldcon in two years, this time to promote The Muppets Take Manhattan. The entire primary cast of The Right Stuff was in attendance, as well as the movie’s inspiration Chuck Yeager. In keeping with a continuing tradition, however, the movie that won the Hugo did not have anyone in attendance to accept the award.

There was little consensus in our group as to what should have won the Hugo for Best Dramatic Presentation in 1982, but we did agree that no matter what won the award, something truly great would be snubbed. Many of us wished The Wrath of Khan could have won, while others felt The Thing should have been honoured.

It was simply a great year for science fiction and fantasy cinema.

I will die on the hill that Bladerunner was the right choice. It's immersive, Scott's best work in my view due to a level of ambiguity that isn't always present in his visions (I'm looking at you Gladiator), and visualized CYBERPUNK in such glorious (and soggy) strokes that haven't been matched.

ReplyDeleteIf you weren't nine in 1982, you might not appreciate what a mind-bender it was to be introduced to the completely foreign term "extra-terrestrial," and how singularly E.T. stands out from every alien life form ever depicted on screen up to that point, and for that matter most of them since. I respect the gamut of SFF films released in 1982, but I think you could run the audience test over and over if the films had been released in subsequent years, and Blade Runner would be buried again and again. If I had to watch one of them tonight, it would be The Thing or E.T.

ReplyDeleteI have a huge soft spot for E.T., though I have to concede that I first saw it as a kid. I do think that E.T. was revolutionary for its time, though. Close Encounters was a movie ultimately for adults; I don't think a movie like E.T., a sci-fi flick written from the perspective of children and treating their concerns with weight, had really existed before, at its scale? I could be incorrect about that, but E.T. feels like ground-zero for all those genre kids' flicks from the 80s and 90s that filled up VHS collections. I've heard other say it hasn't aged well, but I wonder if that's a side effect of viewing it through the eyes of an adult, in a post-Stranger Things world where the suburban 1980's nostalgia it's emblematic of feels played out.

ReplyDeleteI do agree that Blade Runner was the worthy winner. Though, I've always wondered about this win. In its original theatrical run, didn't Blade Runner have a monologue from a frustrated Harrison Ford outlining Deckard's thoughts, alongside a tacked-on happy ending? The director's cut wasn't available until over a decade later. Maybe Blade Runner was such an achievement that fans and voters were able to look past those little quibbles. I'm interesting in how often those details were brought up in fanzine reviews either for or against the film.

On "The Thing": as cool as it would've been to see it in the shortlist and as much as it's an agreed-upon classic now, the film was too critically maligned at the time for that to happen. The common word at the time was that the film was "too gory" to the point where it was hard to get invested in the characters, making the film "boring."

ReplyDeleteI don't think I buy that, especially as the 80s would become infamous for its cinematic bloodfests. I think it's more that a film as dark as The Thing, released two whole weeks after a certain other, more hopeful and whimsical alien film, just didn't jive well with the dawn of the "Morning in America" 80's. It was built on a style of nihilism that had been common in cinema in the last decade but was gradually going out of style by its end, especially in mainstream genre films. On top of that, it was constantly compared unfavorably to the earlier "The Thing from Another World," a far less faithful adaptation of John Campbell's short story that took out all the themes of paranoia. It feels like reviews and takedowns of the film from the time are all dancing around the bottom line: the film just plain bummed them out and they didn't like that. Ironically, now the 1951 film's aged less gracefully.

There lies a flaw with voting in these types of awards: they're tied to the current moment, and how things are perceived in such. Maybe in 40 years, people will look back at next year's Hugos and wonder why the hell "Megalopolis" wasn't nominated. (Probably not.)