Edmonton-based book club that reads and reviews new books in science fiction in an effort to contribute positively to discussions about Hugo Award nominating and voting. The Unofficial Hugo Book Club Blog was established and is maintained by Olav Rokne and Amanda Wakaruk. Most posts are co-authored by Olav and Amanda with input and/or collaboration from other book club members. Guest posts are welcome.

Wednesday, 30 November 2022

Tuesday, 15 November 2022

Battle of the Vonneguts - Hugo Cinema 1973

This blog post is the sixteenth in a series examining past winners of the Best Dramatic Presentation Hugo Award. An introductory blog post is here.

Almost three thousand fans had made their way to Canada’s largest city for the 31st World Science Fiction Convention; a crowd that far eclipsed any previous Worldcon.

|

| The stump of the CN Tower in August, 1973 as seen from near the Worldcon convention hotel. (Image via CBC) |

Looming over the proceedings was “the stump” of the CN Tower. The first few hundred meters of what would one day be the tallest building on the planet was slowly reaching to the sky a few blocks from the convention.

In a frescoed ballroom where Queen Elizabeth II had danced only a few short weeks prior to the Worldcon during her tour of Canada, two thousand fans (two thirds of the convention) squeezed in to catch an early glimpse of a highly-anticipated new animated Star Trek series for which associate producer Dorothy Fontana had brought an advance copy.

Dramatic presentations themselves clearly held an appeal to Hugo voters, though the award itself remained somewhat scorned. At that year’s ceremony, Best Dramatic Presentation seemed somewhat of an afterthought. Which is a shame, as it was a fairly good year for science fiction and fantasy cinema. Even the worst entry on the ballot was generally tolerable.

Unusually, two movies shared at least some of the same source material; both the mainstream hit Slaughterhouse Five and the ultra-low-budget Between Time and Timbuktu are based in whole or in part on Kurt Vonnegut’s 1969 bestseller (also Slaughterhouse Five, though to be fair the latter uses very little of the novel). Despite this unique circumstance, it appears that neither Vonnegut nor anyone involved with either production was in attendance for the Hugo Awards ceremony.

In a frescoed ballroom where Queen Elizabeth II had danced only a few short weeks prior to the Worldcon during her tour of Canada, two thousand fans (two thirds of the convention) squeezed in to catch an early glimpse of a highly-anticipated new animated Star Trek series for which associate producer Dorothy Fontana had brought an advance copy.

Dramatic presentations themselves clearly held an appeal to Hugo voters, though the award itself remained somewhat scorned. At that year’s ceremony, Best Dramatic Presentation seemed somewhat of an afterthought. Which is a shame, as it was a fairly good year for science fiction and fantasy cinema. Even the worst entry on the ballot was generally tolerable.

Unusually, two movies shared at least some of the same source material; both the mainstream hit Slaughterhouse Five and the ultra-low-budget Between Time and Timbuktu are based in whole or in part on Kurt Vonnegut’s 1969 bestseller (also Slaughterhouse Five, though to be fair the latter uses very little of the novel). Despite this unique circumstance, it appears that neither Vonnegut nor anyone involved with either production was in attendance for the Hugo Awards ceremony.

|

| Slaughterhouse Five is a beloved adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut's most famous work, but in some ways it has aged poorly, particularly in terms of sexism. (Image via Guardian.co.uk) |

In fact, nobody from any of the finalist Dramatic Presentations were in attendance. Not The People author Zenna Henderson, not Silent Running script writer Steven Bochco, not even Silent Running director Douglas Trumbull who spent that week at the CFTO-TV Studios in Scarborough, barely 15 miles from the Worldcon.

In what may be one of the most eccentric selections in Hugo Award history, voters selected the television movie Between Time and Timbuktu. It is a chaotic and ultimately disappointing PBS television movie that stitches together various scenarios from essentially every major Vonnegut work up to that point including Cat’s Cradle, Harrison Bergeron, Happy Birthday, Wanda June, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, The Sirens of Titan, Welcome to the Monkeyhouse, and Slaughterhouse Five.

The overarching plot is that Stoney Stephenson (William Hickey) — a poet in modern-day America — wins a contest to travel into space, and on that trip he gets thrown into a dozen different parallel realities. In each of these realities, the viewer gets a brief glimpse of a better and more coherent movie that might have been.

Between Time and Timbuktu might be an obtuse and often irritating movie, but one has to admire the fannish exuberance that must have led a group of public broadcasting employees to create this. It’s clearly made by people who love every word typed by Kurt Vonnegut Jr., but who have no budget to bring those words to life, and no discipline to bring coherence to the script.

A more successful Vonnegut adaptation is Slaughterhouse Five, based on the author’s semi-autobiographical anti-war novel that was shortlisted for the Hugo in 1970. Told in non-linear order, the movie chronicles Billy Pilgrim as he slips forwards and backwards in time to experiences in the fire bombing of Dresden, to his marriage and suburban post-war life, to his abduction by aliens in the 1960s. It’s a piece of speculative fiction that was important in its day, and it’s difficult to complain too bitterly about the fact that the movie won the Hugo Award; at least two members of our cinema club hold it in some reverence.

Non-linear storytelling is especially difficult in cinema, so the fact that director George Roy Hill manages to make it both comprehensible and engaging is commendable. Michael Sacks brings an abiding humanity to the lead role. Miroslav Ondříček’s cinematography is painterly and draws in the eye. And the soundtrack by Glenn Gould is extraordinary.

But in many ways, the film version of Slaughterhouse Five has aged poorly; the depiction of women is demeaning and unpleasant to watch. Most of all, the fat shaming of Billy Pilgrim’s wife, and Pilgrim getting ‘rewarded’ with a young woman upon his wife’s demise, are beyond objectionable.

Based on the short stories by Zenna Henderson, The People was the ABC TV movie of the week on January 22, 1972. It’s a somewhat ham-handed production about a school teacher (played by Kim Darby) who is sent to what appears to be an anabaptist community that eschews technology. Over the course of the movie, she discovers that the residents are in fact telepathic aliens who fled the destruction of their planet. The conflict in the story — such as it is — involves tension within the alien society about whether or not to continue hiding their true selves. William Shatner’s role as the community doctor is one of his least Shatnery performances, but it’s also among his least memorable. This is probably the weakest finalist of that year.

Of this shortlist, most of our cinema club would have voted for Silent Running. The directorial debut of special effects wizard Douglas Trumbull is a slow, weird little movie about Freeman Lowell (Bruce Dern), an ecologist on a spaceship who is tasked with preserving the planet’s last-remaining forests that have been launched into orbit for safekeeping. It’s a fairly flimsy set up, but it provides compelling drama based around moral dilemmas that occur when politicians order Lowell and his crewmates to scuttle the ship. There’s some grey area in these questions; is it appropriate for Lowell to murder his crewmates to preserve the lives of trees and wild animals? Is Lowell correct to disobey unjust orders in the first place?

The movie’s helper robots Huey, Dewey, and Louie, are among the most memorable robots in all of science fiction cinema; as actors Mark Persons, Steven Brown and Cheryl Sparks manage to imbue them with a subtle empathy and dignity.

Trumbull’s filmmaking is technically excellent, both on the interior shots, and the special effects. Compounded with good performances and an absolutely killer Joan Baez soundtrack, Silent Running is a movie that looks better with each passing year.

But there is one omission from the shortlist that is somewhat galling. One science fiction movie in 1972 towers above all the others: Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris. Based on a novel by Polish author Stanisław Lem, the movie follows Kris Kelvin, a psychologist sent to investigate occurrences on a remote research station orbiting a planet that is the movie’s namesake. When he arrives on the station, he discovers that one of the three scientists posted there has died, and the other two are in turmoil. The movie slowly reveals that the planet they’re orbiting is alive, and is sending manifestations to the station, possibly in an attempt to understand humans.

Many have argued that Solaris is one of the finest pieces of science fiction ever brought to the screen, so its complete absence from the Hugo ballot is somewhat baffling. It won awards at Cannes and at the Chicago International Film Festival. It was contemporaneously reviewed in Fanzines such as Norstrilian News and Zimri. Brian Aldis suggests that “it bids fair to stand as the best science fiction film so far.”

The movie is filled with nuance and emotional interiority, as layers of the characters are revealed through their pasts, through the psychological turmoil that the planet’s manifestations cause them, and through the difficult decisions they must make. There’s also an interesting tension between the protagonist’s rationalist worldview, and his desire to believe his deceased wife has been returned to him. It’s a compelling piece of cinema, and should have been a frontrunner for a Hugo Award in any year it was eligible.

The Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation in 1973 had one of the more credible winners, and one of the better shortlists to date. But the omission of Solaris brings the whole enterprise of recognizing the “best” science fiction cinema into question.

In what may be one of the most eccentric selections in Hugo Award history, voters selected the television movie Between Time and Timbuktu. It is a chaotic and ultimately disappointing PBS television movie that stitches together various scenarios from essentially every major Vonnegut work up to that point including Cat’s Cradle, Harrison Bergeron, Happy Birthday, Wanda June, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, The Sirens of Titan, Welcome to the Monkeyhouse, and Slaughterhouse Five.

The overarching plot is that Stoney Stephenson (William Hickey) — a poet in modern-day America — wins a contest to travel into space, and on that trip he gets thrown into a dozen different parallel realities. In each of these realities, the viewer gets a brief glimpse of a better and more coherent movie that might have been.

Between Time and Timbuktu might be an obtuse and often irritating movie, but one has to admire the fannish exuberance that must have led a group of public broadcasting employees to create this. It’s clearly made by people who love every word typed by Kurt Vonnegut Jr., but who have no budget to bring those words to life, and no discipline to bring coherence to the script.

A more successful Vonnegut adaptation is Slaughterhouse Five, based on the author’s semi-autobiographical anti-war novel that was shortlisted for the Hugo in 1970. Told in non-linear order, the movie chronicles Billy Pilgrim as he slips forwards and backwards in time to experiences in the fire bombing of Dresden, to his marriage and suburban post-war life, to his abduction by aliens in the 1960s. It’s a piece of speculative fiction that was important in its day, and it’s difficult to complain too bitterly about the fact that the movie won the Hugo Award; at least two members of our cinema club hold it in some reverence.

Non-linear storytelling is especially difficult in cinema, so the fact that director George Roy Hill manages to make it both comprehensible and engaging is commendable. Michael Sacks brings an abiding humanity to the lead role. Miroslav Ondříček’s cinematography is painterly and draws in the eye. And the soundtrack by Glenn Gould is extraordinary.

But in many ways, the film version of Slaughterhouse Five has aged poorly; the depiction of women is demeaning and unpleasant to watch. Most of all, the fat shaming of Billy Pilgrim’s wife, and Pilgrim getting ‘rewarded’ with a young woman upon his wife’s demise, are beyond objectionable.

Based on the short stories by Zenna Henderson, The People was the ABC TV movie of the week on January 22, 1972. It’s a somewhat ham-handed production about a school teacher (played by Kim Darby) who is sent to what appears to be an anabaptist community that eschews technology. Over the course of the movie, she discovers that the residents are in fact telepathic aliens who fled the destruction of their planet. The conflict in the story — such as it is — involves tension within the alien society about whether or not to continue hiding their true selves. William Shatner’s role as the community doctor is one of his least Shatnery performances, but it’s also among his least memorable. This is probably the weakest finalist of that year.

|

| Silent Running is an innovative and oddball classic that provides memorable characters both human and robot. To be blunt, it rules. (Image via IMDB) |

The movie’s helper robots Huey, Dewey, and Louie, are among the most memorable robots in all of science fiction cinema; as actors Mark Persons, Steven Brown and Cheryl Sparks manage to imbue them with a subtle empathy and dignity.

Trumbull’s filmmaking is technically excellent, both on the interior shots, and the special effects. Compounded with good performances and an absolutely killer Joan Baez soundtrack, Silent Running is a movie that looks better with each passing year.

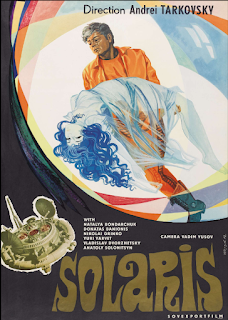

But there is one omission from the shortlist that is somewhat galling. One science fiction movie in 1972 towers above all the others: Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris. Based on a novel by Polish author Stanisław Lem, the movie follows Kris Kelvin, a psychologist sent to investigate occurrences on a remote research station orbiting a planet that is the movie’s namesake. When he arrives on the station, he discovers that one of the three scientists posted there has died, and the other two are in turmoil. The movie slowly reveals that the planet they’re orbiting is alive, and is sending manifestations to the station, possibly in an attempt to understand humans.

|

| Solaris was well-known to SFF fans in the 1970s, but somehow it didn't ever appear on a Hugo award ballot. (Image via IMDB) |

Many have argued that Solaris is one of the finest pieces of science fiction ever brought to the screen, so its complete absence from the Hugo ballot is somewhat baffling. It won awards at Cannes and at the Chicago International Film Festival. It was contemporaneously reviewed in Fanzines such as Norstrilian News and Zimri. Brian Aldis suggests that “it bids fair to stand as the best science fiction film so far.”

The movie is filled with nuance and emotional interiority, as layers of the characters are revealed through their pasts, through the psychological turmoil that the planet’s manifestations cause them, and through the difficult decisions they must make. There’s also an interesting tension between the protagonist’s rationalist worldview, and his desire to believe his deceased wife has been returned to him. It’s a compelling piece of cinema, and should have been a frontrunner for a Hugo Award in any year it was eligible.

The Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation in 1973 had one of the more credible winners, and one of the better shortlists to date. But the omission of Solaris brings the whole enterprise of recognizing the “best” science fiction cinema into question.

Thursday, 10 November 2022

Space Nazis Must Die

Hitler’s goon squad casts a long shadow over science fiction.

It’s easy to see the outline of Nazi soldiers in the Impirial Military of Star Wars, Doctor Who’s Daleks, The Alliance in Firefly, or the Terran Federation shock troops in Blake’s 7.

Deliberate choices are made in films to offer the connotation of Nazi, often including immaculately tailored Hugo-Boss-style uniforms, Teutonic heel taps of the jackboots when marching, and Riefenstahllian visuals of parade grounds and iconic banners. Sometimes, there’s a suggestion that these fictional soldiers are motivated by some form of racist ideology, though the details of this are usually nebulous.

Let’s be clear here: Nazis are bad.

Nazis should be opposed wherever they exist: on the battlefield, at the ballot box, in the streets, and across the tenebrous depths of interstellar space. As such, depicting villains as Nazis — and therefore Nazism as villainous — has value.

But depiction without engaging with the premises of motivation is lacking. “Nazi” is such an easy signifier for evil, it often allows these narratives to avoid engaging with what evil actually means. Sure, Imperial Soldiers kill a lot of people in the Empire Strikes Back, but so do the zombies in Train to Busan, or the tornado in Twister, or the Xenomorphs in Alien. The faceless hordes provide little more than target practice for laser rays; there’s no interiority behind the mirrorshades and white perspex armour.

|

| “We will fight them on the beaches...” (Image via IMDB.com) |

It’s easy to see the outline of Nazi soldiers in the Impirial Military of Star Wars, Doctor Who’s Daleks, The Alliance in Firefly, or the Terran Federation shock troops in Blake’s 7.

Deliberate choices are made in films to offer the connotation of Nazi, often including immaculately tailored Hugo-Boss-style uniforms, Teutonic heel taps of the jackboots when marching, and Riefenstahllian visuals of parade grounds and iconic banners. Sometimes, there’s a suggestion that these fictional soldiers are motivated by some form of racist ideology, though the details of this are usually nebulous.

Let’s be clear here: Nazis are bad.

Nazis should be opposed wherever they exist: on the battlefield, at the ballot box, in the streets, and across the tenebrous depths of interstellar space. As such, depicting villains as Nazis — and therefore Nazism as villainous — has value.

But depiction without engaging with the premises of motivation is lacking. “Nazi” is such an easy signifier for evil, it often allows these narratives to avoid engaging with what evil actually means. Sure, Imperial Soldiers kill a lot of people in the Empire Strikes Back, but so do the zombies in Train to Busan, or the tornado in Twister, or the Xenomorphs in Alien. The faceless hordes provide little more than target practice for laser rays; there’s no interiority behind the mirrorshades and white perspex armour.

Using the symbolic Nazi provides a type of worldbuilding and character shorthand for the viewer, or reader. It conveys a (false) dichotomy that provides comfort; a comfort in knowing that Nazi = bad and the other side = good. It gives the consumer a break from having to figure out bad from good for themselves.

Science fiction’s depiction of fascism and of fascists is occasionally more pointed and valuable. Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers plays a brilliant bit of sleight of hand, first building up the Terran Federation as a heroic force through propaganda techniques, then slowly revealing to the audience that they’ve been duped into cheering for Nazis. Norman Spinrad’s The Iron Dream explores how heroic fantasy narratives are rooted in similar assumptions to the mythologized history that underpin fascist mythmaking. And Vernor Vinge’s Deepness In The Sky explores new ways for human freedom to be subverted by Nazis.

But the predominant conception of Nazis in science fiction is little more than a costume.

Consider: there are overt and unrepentant real-world fascists who are die-hard Star Wars fans. But we wonder – do they see the linkage? The classic trilogy encourages such minimal critical engagement that it would be easy to imagine someone spending a day at a polling station with an assault rifle intimidating BIPOC voters and then go home and watch the Special Edition of A New Hope and cheer for the Rebellion. Likewise, it’s not uncommon to see left-wing pro-democracy activists involved in

the 501st Legion and dressing up as fascist Stormtroopers on a regular basis. This is not to play any false equivalence between these two groups; but rather to point out how vague and tenuous the depiction of fascism has traditionally been in Star Wars and how this leaves the viewer free to engage with its narratives at a superficial level.

And all of this is why the most recent iteration of Star Wars is so refreshing. Andor presents a multi-layered view at the Empire that explores the seductive power that authoritarian systems can have on their participants: the capitalist class that profits from oppression and is lulled by the illusion of security; the mid-level bureaucrats who fetishize order and see the opportunity for advancement; the ground-level workers who sell out their peers just to escape the butcher’s block for another day. At the risk of hyperbole, it sometimes feels as if the series is building a taxonomy of fascists; an Audubon Guide to the Nazis In Our Midst.

Andor suggests that there is no one type of fascist in the Star Wars universe, and in doing so makes the empire more believable, and the imperial system to be far scarier. The genre needs more of this. These may be stories that are often set in a galaxy far, far, away … but fascism is never as distant as it should be.

|

| Nazi-coded villains can be found in all kinds of SFF from Star Wars to Planet of the Apes to Woody Allen’s Sleeper. But do these movies invite the viewer to consider what this iconography means? (Image via Overture Magazine) |

Science fiction’s depiction of fascism and of fascists is occasionally more pointed and valuable. Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers plays a brilliant bit of sleight of hand, first building up the Terran Federation as a heroic force through propaganda techniques, then slowly revealing to the audience that they’ve been duped into cheering for Nazis. Norman Spinrad’s The Iron Dream explores how heroic fantasy narratives are rooted in similar assumptions to the mythologized history that underpin fascist mythmaking. And Vernor Vinge’s Deepness In The Sky explores new ways for human freedom to be subverted by Nazis.

But the predominant conception of Nazis in science fiction is little more than a costume.

Consider: there are overt and unrepentant real-world fascists who are die-hard Star Wars fans. But we wonder – do they see the linkage? The classic trilogy encourages such minimal critical engagement that it would be easy to imagine someone spending a day at a polling station with an assault rifle intimidating BIPOC voters and then go home and watch the Special Edition of A New Hope and cheer for the Rebellion. Likewise, it’s not uncommon to see left-wing pro-democracy activists involved in

|

| The fascist tendency to view human beings as tools, and the prison system as a source of expendable labour is depicted well in Andor. Some fans didn’t get the message. (Image via Polygon) |

the 501st Legion and dressing up as fascist Stormtroopers on a regular basis. This is not to play any false equivalence between these two groups; but rather to point out how vague and tenuous the depiction of fascism has traditionally been in Star Wars and how this leaves the viewer free to engage with its narratives at a superficial level.

And all of this is why the most recent iteration of Star Wars is so refreshing. Andor presents a multi-layered view at the Empire that explores the seductive power that authoritarian systems can have on their participants: the capitalist class that profits from oppression and is lulled by the illusion of security; the mid-level bureaucrats who fetishize order and see the opportunity for advancement; the ground-level workers who sell out their peers just to escape the butcher’s block for another day. At the risk of hyperbole, it sometimes feels as if the series is building a taxonomy of fascists; an Audubon Guide to the Nazis In Our Midst.

Andor suggests that there is no one type of fascist in the Star Wars universe, and in doing so makes the empire more believable, and the imperial system to be far scarier. The genre needs more of this. These may be stories that are often set in a galaxy far, far, away … but fascism is never as distant as it should be.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

-

Organized labour in science fiction LIST AS SORTABLE EXCEL DOCUMENT Additional suggestions are welcome. This li...

-

The following list will be updated over the next few months as we read, watch, and listen to Hugo-eligible works for 2026. These are not nec...

-

It is quite possible that there are more printed copies of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire than of all other Hugo Award winners put tog...