Political debates have simmered throughout the history of the Hugo Awards. This is because in some ways, science fiction is a more political form of literature than other genres.

You cannot write about imaginary futures and different worlds without showing how their societies are different than our own; how they are better and how they are worse. In this sense, as others have observed, science fiction is a medium of utopias and dystopias. And the determination of what makes a society dystopic or utopic is inherently about political values.

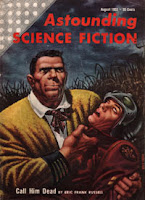

|

| Fascists, communists, libertarians and religious groups have all embraced the power of science fiction to shape society's view of the future. (Image via Collider.com) |

If you believe that all humans are really created equal, your utopia likely won’t include a caste system. If you believe that humans have a right to privacy, a government surveillance state will be depicted as a dystopia. If you believe that the world needs racial purity and genetically superior heroes to save us from corruption, you might write a fantasy about a man of high Númenórean blood who is destined to reclaim the Throne of Gondor.

These are all political beliefs.

Practical politics is about changing the world. Science fiction is about exploring worlds that have been changed. The two are intertwined.

This is what the Futurians and their critics at the first Worldcon all understood: By imagining utopias

|

| In the 1930s, Futurians (including Cyril Kornbluth, Chester Cohen, John Michel, Robert Lowndes and Donald Wollheim) argued that SF has a responsibility to help guide the way to better tomorrows. |

This political nature of science fiction is one of the reasons that political campaigning and organizing to promote a Hugo Award contender have been with us since the moment the awards were announced.

In early August 1953, Will Jenkins, one of the organizers of the First Annual Achievement Awards In Science Fiction (which would later become known as the Hugo Awards), endorsed political campaigning for the award, writing in the fourth progress report for the Worldcon in Philadelphia “There is still time to do a little campaigning to line up a solid bloc of votes for your favourites.”

The subsequent year, organized campaigning probably played a significant part in the honouring of oft-criticized second Hugo-winner They’d Rather Be Right. The book, which veers between

|

| Image via Goodreads.com |

The committee organizing the Hugo Awards responded to the They’d Rather Be Right debacle by screening all nominations in 1956 through a “special committee to determine their qualifications.” While it’s good that this anti-democratic jurying did not become a permanent part of the Hugo Awards process, the fundamental issues of political factions was never fully addressed, and tensions simmered.

Over most of the history of the awards, these rivalries have been benign; such as during

|

| The environmental activism of Rachel Carson and her book Silent Spring inspired 1977 Hugo Winner Where Late The Sweet Birds Sang. (Image via island conservation.org) |

While the dispute was heated, nobody tried to claim the award was invalid, or tried to wreck the system. The argument was no longer a factor by the time Fred Pohl won for Gateway the next year.

Recent winners are neither uniform in their politics, nor narrow in their possible interpretations. There is an enormous ideological gulf between the The Fifth Season’s skepticism towards clerical authority, and the triumphalist worldview of The Three-Body Problem.

Both novels won in part because of how skillfully their authors built a utopia or dystopia from the philosophical underpinnings they believed in. Both novels are worthy winners that should be celebrated.

Today’s heated discourse over the futures that science fiction imagines — and creates potential blueprints for — must be seen in the context of science fiction’s inherent political nature.