|

| (image via Goodreads) |

Babel — the latest novel from Astounding Award-winner R.F. Kuang — seems to fit this definition. It may also be the most McLuhanesque fantasy novel ever written.

Set in 1830s England, Babel follows a Cantonese orphan Robin Swift who is recruited to work for Oxford’s translation department in a world in which the translation of words from one language to another can have mystical consequences. The enchantment of translation has become crucial to England’s ability to colonize and exploit much of the globe, as silver bars inscribed with words in multiple languages can manifest the meaning that is ‘lost’ in translation. The United Kingdom has a near monopoly on this magical technology, and Oxford is at the heart of the Empire’s power.

There’s a long tradition in genre literature of the British historical fantasy as a particularly escapist work. Stories during the Napoleonic War, or the Victorian Era, can provide a cozy and comfortable setting that’s often insulated from vital questions of equity between those of differing racial groups, social classes, and genders. This is not to dismiss these works — as escapism has its place — but this peculiar form of nostalgia can conveniently edit or omit important issues of social justice. Babel, however, does not shy away from any of the injustices of the timeframe it is set in, but rather confronts them head-on. It would take more than magic, the book seems to suggest, to make a fairer, more just world.

This is a novel that uses the form of Regency-era historical fantasy to tackle themes of social justice that are at the forefront of today’s cultural vanguard in science fiction and fantasy. In short, it uses the cultural precepts of England at the peak of its colonial power to disclose and critique the social impacts of those systems.

It’s worth noting that although many American authors have attempted to mimic the style of period British prose, the vast majority have failed, often sounding affected, or pompous, or leaden. But instead of clumsy pastiche, Babel feels like a fantasy that William Makepeace Thackeray might have written. Kuang evokes era-appropriate ambiance and regionally-believable prose and dialogue so skillfully that we double-checked to see if she was born and raised in Hertfordshire or Dorset. (We strongly encourage everyone to read the “Author’s Note on Her Representations of Historical England, and of the University of Oxford in Particular,” which precedes the text of the novel.) It is especially gratifying that a book that is deeply concerned with language as a concept uses it so skillfully.

|

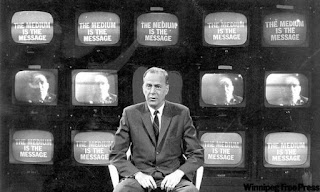

| “All words, in all languages are metaphors,” wrote Marshall McLuhan — a sentiment that might resonate with the protagonists of Babel. (Image via University of Toronto) |

Central to the themes in the book are the three close friends that Swift makes at Oxford. Victoire Desgraves, Letitia (Letty) Price, and Ramiz (Ramy) Mirza are — like Swift — translation students who are alienated from their peers for reasons related to race, class, gender, or a combination of these. Calcutta-born Ramy and Haitian-born Victoire keenly feel the animosity directed towards them by racist and classist rich white students, though Letty, who is white herself, never seems to understand or to see what her friends are going through.

About a decade ago, psychological researchers in Texas examined how the grammatical patterns that individuals use are a strong predictor of romantic attraction and relationship stability. The possible explanation they offered was that similar patterns and order of functional words (prepositions, articles, quantifiers, high-frequency adverbs, etc.) probably reflect similar patterns of thought … and can therefore be a signifier of the potential for meaningful relationships. Interestingly, this seems to be true across languages. Rami and Robin — whose life stories parallel each other in myriad ways — speak the same language of love and of friendship, and reminded some of us of this research. Their attraction, though never explicitly spelled out, is an emotional backbone of the novel. As much as many readers (us included) would love for their romance to play out more happily, there is a certain degree of integrity to depicting the characters as being prisoners of the heteronormative homophobia of the 19ᵗʰ century.

Language can also act as a barrier, even among those who speak the same one. For much of the novel, working-class characters are given short shrift. Striking labourers are depicted as speaking incoherently, and their concerns are dismissed by Robin, Rami, Victoire and Letty. But then the novel pulls a nice piece of narrative revelation; showing that even the protagonists can be unaware of matters of social justice, and that allyship can be found in less-expected places. Labour unions — including the Oxford Translators Union — become vehicles for solidarity and for bridging cultural divides.

After three excellent novels, R.F. Kuang had already established herself as one of the best young writers in genre fiction. With Babel, she has taken her work to a new level.

About a decade ago, psychological researchers in Texas examined how the grammatical patterns that individuals use are a strong predictor of romantic attraction and relationship stability. The possible explanation they offered was that similar patterns and order of functional words (prepositions, articles, quantifiers, high-frequency adverbs, etc.) probably reflect similar patterns of thought … and can therefore be a signifier of the potential for meaningful relationships. Interestingly, this seems to be true across languages. Rami and Robin — whose life stories parallel each other in myriad ways — speak the same language of love and of friendship, and reminded some of us of this research. Their attraction, though never explicitly spelled out, is an emotional backbone of the novel. As much as many readers (us included) would love for their romance to play out more happily, there is a certain degree of integrity to depicting the characters as being prisoners of the heteronormative homophobia of the 19ᵗʰ century.

Language can also act as a barrier, even among those who speak the same one. For much of the novel, working-class characters are given short shrift. Striking labourers are depicted as speaking incoherently, and their concerns are dismissed by Robin, Rami, Victoire and Letty. But then the novel pulls a nice piece of narrative revelation; showing that even the protagonists can be unaware of matters of social justice, and that allyship can be found in less-expected places. Labour unions — including the Oxford Translators Union — become vehicles for solidarity and for bridging cultural divides.

After three excellent novels, R.F. Kuang had already established herself as one of the best young writers in genre fiction. With Babel, she has taken her work to a new level.